A Brief Geologic History of Wisconsin

- Jason G. Freund

- Nov 2

- 7 min read

I feel compelled to begin this with stating that I am NOT a geologist, and geologic history is an interest, not an occupation. The concept of "deep time", that is thinking about events that go back hundreds of millions or even multiple billions of years, is simple fascinating and hard to get one's mind around. And what happened billions of years ago continues to have an effect and been seen today. That idea is pretty crazy to me - and certainly worth further exploration.

The oldest rocks in Wisconsin go back about 3 billion years, the youngest rocks that are widespread - the Niagara Escarpment - are about 420 million years old. We are not far from Michigan's Upper Peninsula where the oldest rocks in the United States exist (see video near end of this post for details). Younger Devonian ("the age of fishes") geology is present along a small bit of Lake Michigan, but rarely are these rocks not covered by glacial drift. In fact, these fossilized coral reefs (yes, there were coral reefs in Wisconsin) are most seen in quarries or road cuts in southeastern Wisconsin.

Of course, the glaciers have done more to shape Wisconsin than any other phenomena in the last 25,000 or so years - which is a mere blip in terms of the history of the Earth (0.0005% of the Earth's age). One might push that number back to closer to 400 million years. As you will see, not much has happened in Wisconsin these past 400 million years - geologically speaking. While there were other glaciers, the Wisconsin glaciation is so named because Wisconsin is where its effects are most evident. That is because it was the most recent of the several glaciations that once covered the state, minus the Driftless Area.

Much of the geology of Wisconsin is buried under glacial deposits, but in other places, those same glaciers removed younger layers of bedrock to expose the rocks below. And the "true" Driftless Area - like that of (most of) Wisconsin, is not unaffected by the glaciers (we'll talk about that...) but it is much less influenced by them than the rest of the state was. One thing you might be thinking after looking at the map above is that the northwestern part of the Driftless does not seem to be Driftless. And to the northeast, Glacial Lake Wisconsin, an ice age lake occurring on the edge of the Wisconsin Glaciers. The catastrophic failure of this lake is largely responsible for the Dells of the Wisconsin River (more be ).

Source: WDNR Depth to Bedrock. For an even more detailed version of this map, visit the Surficial Deposits map.

The depth to bedrock map above is a good place to start to understand the effects of the glaciers and where you are most likely to be able to see surface bedrock features. It is quite evident that much of Wisconsin's bedrock is deeply buried by glacial drift. For this post, we are "removing" the glacial drift - making all the state Driftless - and looking only at what has been buried. For a more detailed view of the state and its geology, read Dott and Attig's Roadside Geology of Wisconsin, the Wisconsin Geological and Natural History Survey's website, their major landforms of Wisconsin visual story, and Gwen Schultz's Wisconsin's Foundations: A Review of the State's Geology and Its Influence on Geography and Human Activity.

One thing to keep in mind when looking at bedrock maps is that they simply provide the type of rock at or nearest the land's surface. Below the surficial bedrock lies rock layers that are older - the figure below is an example cross-section from along the Mississippi River in Minnesota.

Imagine looking at a Mississippi River bluff and that you know enough about geology to understand what you are looking at...this figure is essentially what you are seeing when looking at a Mississippi River bluff - like Grandad Bluff here in La Crosse - though the cap of this bluff is the older Prairie du Chien Group. The slope of the different layers inform us about the hardness of that rock layer. The St. Peter Sandstone is a relatively soft layer that is more easily eroded than are the surrounding layers. And cap rocks - those at the top of the plateaus - are typically the hardest layer still present as the softer rocks above it have been eroded away.

A Trip Back In Time

With a bit more familiarity with how much of Wisconsin's bedrock geology is "hidden" by glacial drift, let's take another look at the bedrock geology map. To understand time in this map, in the explanation, the top represents the youngest rocks - Devonian dolomite and shale - and the bottom, the oldest rocks - Lower Proterozoic or Upper Archean rocks.

There is a pretty clear time gradient across the state, with the oldest rocks in northern Wisconsin and the youngest rocks occurring along Lake Michigan. The oldest rocks in Wisconsin are in north central Wisconsin are orange (gr) and a sliver of olive green (mv) in the geologic map of Wisconsin. To put things in perspective, the Earth is 4.54 billion years old and the oldest known life dates back to at least 3.6 billion years ago, and maybe up to 4.3 BYA. Our oldest rocks are about two-thirds as old as the Earth. Old rocks - that is, those of more than a billion years old - are rare because plate tectonics means that the deepest rocks are continually, albeit slowly, remelted into the mantle. This is part of the rock cycle. (For a Geological map with more details about the rocks and their ages.)

Image source: https://www.nps.gov/subjects/geology/time-scale.htm

Deep time is probably one of the most difficult concepts for us to get our minds around. The numbers are nearly incomprehensible and the conditions on Earth were nothing like they are currently. For example, when our state's youngest rocks were formed, fishes were less than 50 million years old, amphibians were evolving, dinosaurs were 200 million years in the future, and mammals were about 300 million years into the future. To put that in perspective, assuming a human life expectancy of 80 years, 300 million years is 3.75 million lifetimes. If we put the earliest known life at 4.3 billion years ago (it may be as "young" as 3.6 billion years), that is 53.75 million human lifetimes. It would take you over 135 years to count to 4.3 billion - but no pauses or it would take longer. Counting to 400 million, the last time something interesting happened in Wisconsin, would take you not quite 13 years. At this time, Wisconsin was near the equator - about 20 degrees south latitude - and most of the state was a shallow, tropic sea. In fact, just north of Milwaukee, coral reefs provide evidence of this bit of our history.

The video above put many events within geologic time in perspective.

The Rock Cycle

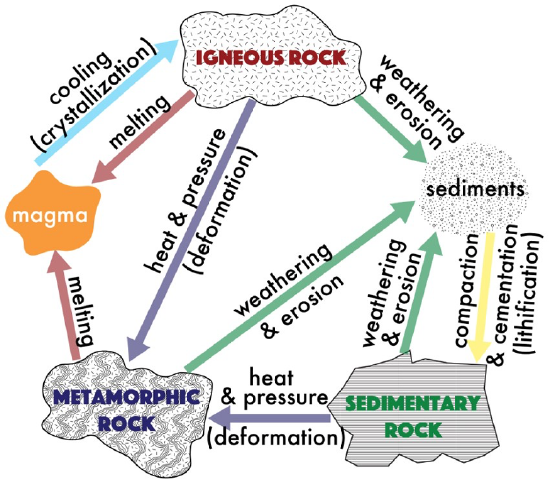

The rock cycle describes how rocks are created and altered over their lives. There are three main types of rocks:

Sedimentary - Rocks made of consolidated sediments and are usually described by what sediments the rock is composed of - sandstone, limestone, and shale or mudrock, as examples. Larger sediments - like gravels - can make up conglomerates. These sediments were typically - but not always - moved by and deposited in water.

Igneous - Rock formed by the cooling of magma or lava. Igneous rock is quite variable because of the constituents of the magma or lava and the speed at which it solidified to form solid - rather than liquid - rock. Most igneous rock in intrusive - formed by cooled magma; whereas extrusive rock is formed as lava cools.

Metamorphic - Sedimentary or igneous rock that has been transformed by heat and pressure. The parent rock - protolith - and the combination of temperature and pressure helps determine the type of metamorphic rock created.

The figure above shows the types of rock along with the processes acting on each rock type. For example, weathering and erosion of any type of rock can create sediments which can then be lithified - turned into sedimentary rocks.

Sedimentary rocks are most common - about 75% of the Earth's surface, followed by igneous rocks at about 12 - 15% and metamorphic rocks, which make up about 10% of the Earth's surface. These percentages are about the same in Wisconsin - though 80% sedimentary and a bit less metamorphic rock might be a better estimate.

Geologic Regions of Wisconsin

I will dig deeper into each of these in future posts but, for now, Wisconsin's geographic regions align with the type of bedrock and glacial history. As mentioned previously, northern Wisconsin has the oldest rocks (on average), and is higher in elevation than the rest of the state. The table below is an approximation of these regions, their dominant geology, age of those rocks, and what types of rocks or features are most notable.

Table 1. Regions of Wisconsin, their dominant geology, approximate age, and unique features. Thanks, ChatGPT.

Region | Dominant Geology | Approximate Age | Key Features |

Northern WI | Precambrian shield | 3.0–1.0 billion years | Basalt, granite, gneiss |

Western/Southern WI | Cambrian–Ordovician sedimentary | 500–450 million years | Sandstone, dolostone, fossils |

Eastern WI | Silurian dolostone (Niagara Escarpment) | ~420 million years | Fossils, quarries |

Southwestern WI (Driftless) | Unmodified Paleozoic | 450–400 million years | Deep valleys, exposed cliffs |

Rocks date from around 3 billion years old to about 400 million years old. We have not seen new surface bedrock created in the past 400 million years - that is generally a phenomenon that occurs in more geologically active regions. Aside from the glaciers, Wisconsin and the upper Midwest has been rather stable for a long period of time. That was not always the case.

Sedimentary rocks are the surficial bedrock for most of the state, and these rocks tend to be younger. The sandstones, limestones, and dolostones (dolomite) of the southern two-thirds of the state are examples of sedimentary bedrock. Probably the most unique sedimentary feature of the state is the Niagara Escarpment, which forms the western side of Door County as well as High Cliff State Park and Ledge County Park. Metamorphic rocks make up the Canadian Shield of Northern Wisconsin, as well as the quartzite of the Baraboo Range - home to Devil's Lake, probably the state's most visited geologic feature - and the lesser known Waterloo Quartzite near my hometown. Lastly, igneous rocks are intrusions that make up the Penokee Range and the granites of the Wolf River Batholith.

That's enough for one post. Expect a post about the glacial landscape of Wisconsin and then a fly fishing centric tour of the state, one geographic province at a time.

Thank you, Professor....always an interesting and educational read. I grew up fishing & hunting in the Blue Hills (also known as the Barron Hills) in Rusk & Sawyer Ctys, that geological anomaly was supposedly an ancient mountain range that is a couple billion years old.

Jason: This was extraordinarily interesting and helpful in learning about the geology that gives and sustains our fish. Keep it coming. Jon Christiansen

How do the different types of exposed rocks affect the PH in the streams, rivers and lakes? No mention on the fault lines going across the State of Wisconsin and the mystery of how radon and different gases released along the fault lines affect the weather, our health, our ground water, etc. The radon released into the atmosphere by evapotranspiration by trees is still a mystery to scientists.